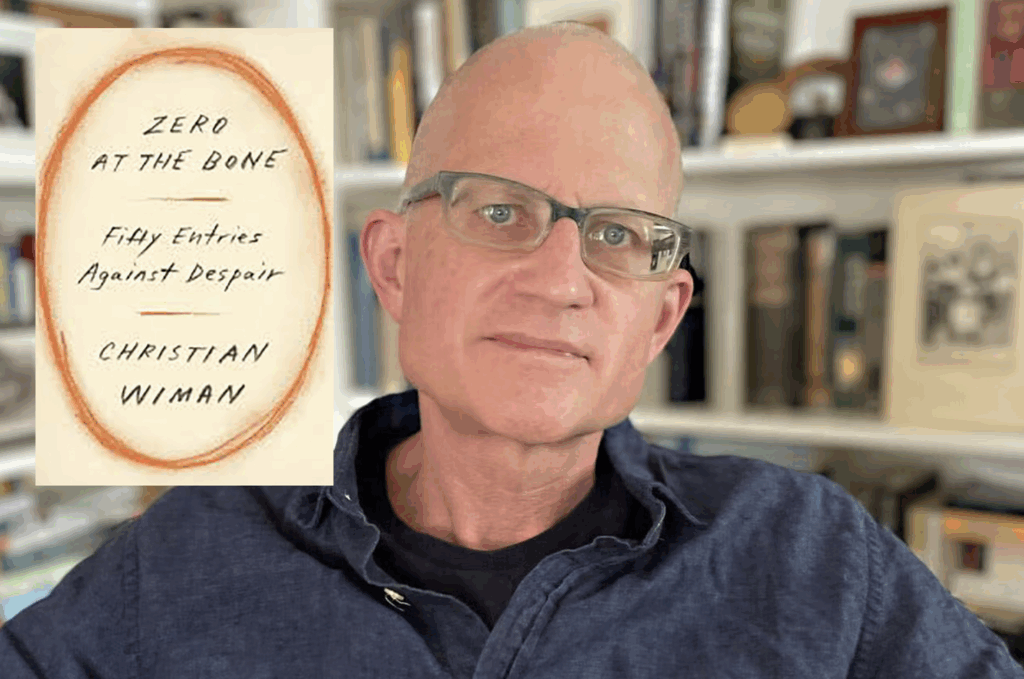

Our recent Rector’s Book Club gathering wrestled with Christian Wiman’s provocative collection of prose and poetry, “Zero at the Bone: Fifty Entries Against Despair.” This was not a pursuit of “easy answers”, but a purposeful effort to push us intellectually and see if we could “crack into some things that are new or interesting or a little bit vital” regarding faith and suffering, Fr. Noah said, introducing the work.

Wiman, known for his rigorous poetry and unflinching look at reality, employs a style that is intensely personal and fiercely honest, described by Fr. Noah in our discussion as “allergic to those easy answers in a violent way.” His work forces readers to ask questions that are real and confront a reality where there are no neat and tidy answers. The book is a blend of forms, reflecting the “storm of forms and needs, the intuitions and impossibilities that I feel myself to be, that I feel life to be,” Wiman writes.

Read the New York Times review of Mr. Wiman’s book here.

Read an interview with Mr. Wiman at the Yale Divinity School’s website here.

Stripped Bare: What is “Zero at the Bone”?

The central, challenging metaphor of the title drove much of our conversation. What exactly does it mean to reach “Zero at the Bone”?

Members found the phrase multifaceted, embracing ambiguity rather than settling for a single definition. For many, it represented a place of utter despair and stripping away all pretenses. As one member said, the title evokes “empty, nothing left” and the feeling that “he’s poured it all out”.

Yet, for a writer deeply engaged with the Christian faith, this nothingness simultaneously suggests the divine. Wiman flirts with nihilism, putting his foot right over the edge, but continually finds things that pull him back to life and beauty.

Our discussion noted that Wiman equates “zero” with God in other parts of the book. Stripping away the superficial layers—the muscle and the viscera—leaves the “bone”. It is in this bare, essential state that one encounters the divine. As one member said, Wiman is getting at how, when you get down to the bone, “that is where you find God.” Wiman himself notes that, when we reach that place of nothingness, we find “not nothingness, but too many meanings.”

“Wiman argues that “one doesn’t follow God in hope of happiness. But because one senses… a truth that renders ordinary contentment irrelevant.”

Awe, Suffering, and the Irrelevance of Contentment

Wiman fundamentally challenges the notion that faith should lead to simple happiness. He recounts a friend asking why people follow a religion that doesn’t make them happy. Wiman argues that “one doesn’t follow God in hope of happiness. But because one senses… a truth that renders ordinary contentment irrelevant.”

The author, a cancer survivor, draws intensely on the realities of suffering, discussing his time in the chemotherapy infusion center and wrestling with the Book of Job. This honesty resonated deeply with our readers. One member said that by reading that scene, they “developed some empathy for his despairing persona”, recognizing Wiman’s commitment to the terrible reality of the situation: “This sucks. This is bad. This is suffering.”

Our discussion highlighted Wiman’s belief that life provides experiences so “all-consuming” that they demand awe. Suffering is often twin to joy, creating experiences that shake us out of complacency. One member said Wiman suggests that joy and suffering are “basically… the same.”

The Miracle of Awkward Connection

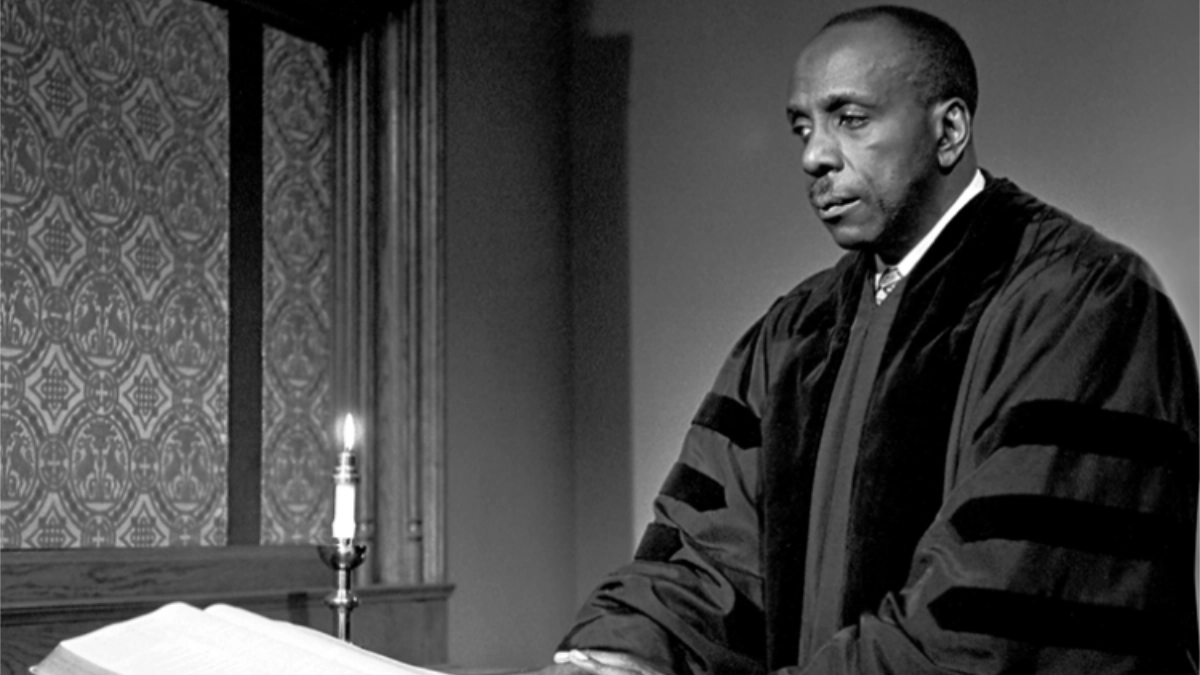

The book club was also spent some time discussing a poem in the book by Etheridge Knight called “ A Wasp Woman Visits a Black Junkie in Prison.”

They are two people who have every reason for the encounter not to work. The poem details their efforts to fish for a denominator, common or uncommon, and how they could only find that both were human.

The breakthrough comes when the incarcerated man breaks the tension by asking the visiting woman about her children. One member said this was “very true of people meeting for the first time in an awkward situation,” searching for a connection. Crucially, Wiman noted that the encounter resulted in “no resurrection, no shackles were shaken“. The miracle was simpler. One member said they liked how the “miracle was just chatting,” a connection found person-to-person through shared vulnerability. This shift —the inmate walks away “softly and for hours used no hot words”—is the quiet work of grace that emerges when we let down our shields.

Embracing Bewilderment

Ultimately, Wiman invites us to embrace ambiguity. He finds poetry so vital because, like God, it resists closure. He argues that the need for “fixities, finalities, poles upon which you can place your hand and say, This I believe” is something we must outgrow. This resonates with a Christian understanding that God is always more, continually calling us to deeper faith and bigger love.

The lack of fixed answers leads to what Wiman names as a spiritual gift. In his penultimate poem, he concludes: “Loss is my gift. Bewilderment my bow”. One member said that this mystery is a “twin to awe,” highlighting that things that cause awe are not necessarily rational. Another saw Wiman’s theological journey reflected in his realization that events can change not only the future but the past, perceiving the past as “plastic.”

The book may be a struggle, but as Wiman reminds us, the purpose of this wrestling is to discover that which endures through chaos and doubt. He closes his book with a profound truth that speaks to the core of enduring faith: “For all that can be shaken will be shaken. And only the unshakable remains”.

If you’ve read this roundup found it interesting, there’s good news! Next month’s book is Heaven and Nature Sing by Hannah Anderson. We’ll discuss it on Friday December 19 at 5 p.m. Please come along!